Mrs. Lawson was no pushover at the short-lived "Sheridan Annex," which burned down.

The downward-sloping lot at the corner of Prospect and Division streets was easy to overlook amid the mansions, schools and structures of Yale University and a low-slung apartment complex. A patch of out-of-season growth, perhaps a community garden, is the site’s only defining characteristic.

“It was right there,” I gestured to my wife, Gina, as we pulled our rental car to the curb after ascending Prospect Street from Sachem Street and the assemblage of mansions and modern structures once accommodating the Yale School of Organization and Management (SOM). Forty years earlier, I had received a master’s degree in public and private management from SOM and departed my native New Haven for career opportunities in Baltimore and Detroit. Though a frequent Elm City visitor, I never sought out the Prospect and Division location – until last month.

The “it” was a tired and creaky mansion hastily painted and dusted during the turbulent summer of 1967 in preparation for receiving perhaps 100 New Haven public school students for the September start of 8th grade.

Though it had no exterior signage, the building and “school” were referred to as the Sheridan Annex.

Within a few months, a suspicious fire forced abandonment of the structure and to the likely embarrassment of idealistic New Haven Public School leaders, relocation to emergency classroom space in … Hamden. By June of 1968, the Sheridan Annex had disappeared, apparently a hush-hush failure of a one-and-done experiment.

After attracting national attention in the mid-1950s and early 1960s for its large, controversial, Yale-influenced efforts at urban renewal, New Haven turned to its public schools. In 1964, its Board of Education and superintendent of schools pushed a far-reaching and complex plan to desegregate its public schools. Following often fierce neighborhood pushback, the plan’s scope was dramatically reduced. According to Gillien Todd in “School Desegregation and the Decline of Liberalism: New Haven, Connecticut in 1964,” the plan would now involve the pairing of two junior high schools, Bassett and Sheridan, that would collectively serve seventh and eighth graders from nine elementary schools in the Westville and Dixwell areas. Through busing Bassett children to Sheridan and Sheridan children to Bassett, the populations at both schools would be racially balanced. In 1963, Bassett’s student population was 90.2% Black and Sheridan’s was 83.7% white.

In September of 1966 I started 7th grade at Sheridan, walking just under a mile from our Chapel Street home to its Fountain Street location. Nearby Edgewood was my elementary school. Though 7th grade had been a mixed-bag experience – some excellent teachers along with periodic fistfights — I was upset when for 8th grade, my parents hastily decided to bus me to the Sheridan Annex. In addition to a 15-minute walk to a bus stop at the foot of Central Avenue and Fountain Street, I would travel an additional 20 minutes or so to this mysterious school. “What were you thinking?” I never thought to ask that question of my parents while they were alive.

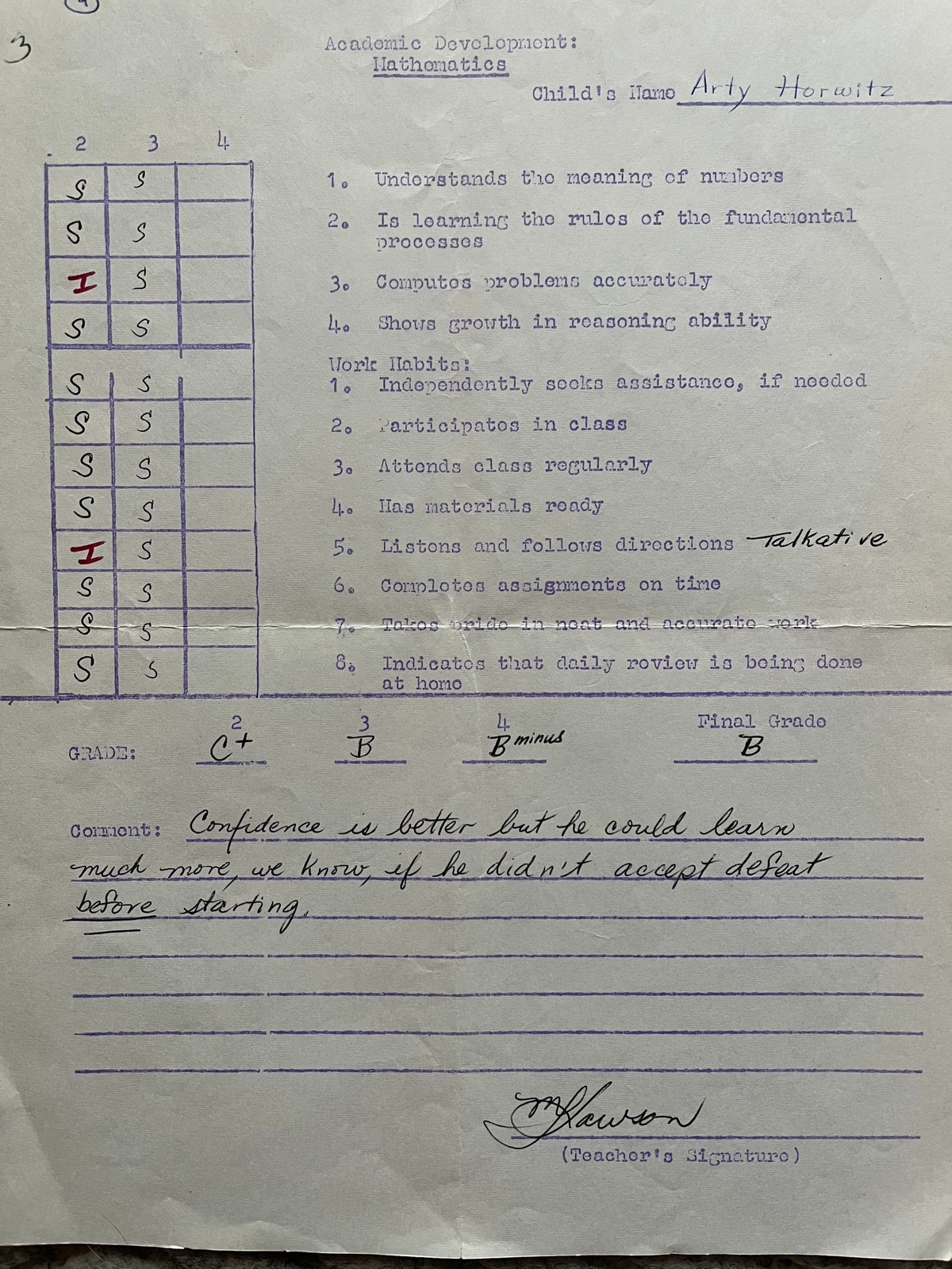

The composition of the student body had telltale signs of a laboratory research experiment. It appeared to be half Black and half white and half female and half male. About half were drawn from Westville and half from Dixwell. Initially, the experiment seemed designed to allow 13- and 14-year-old students to share school governance with its administrators. Except for the time spent in Mrs. Lawson’s math class, I either ran wild or ran scared.

Within the first couple of weeks, the mansion’s garage/carriage house was claimed by a group of students who declared it off limits for Westville students. Our social studies teacher introduced herself the first day as Miss Little “and I don’t take any sassing back.” Well, a chorus of students – myself included – heaped all the sass we could on her until she left the classroom in tears. She never came back. There were no consequences for our actions or attempts at “teachable moments.” The only useable space for outdoor recreational purposes was a small, uneven lot where two-handed touch football games often devolved into punching and group fights. Rainy days meant we could use an indoor basketball court at the nearby Yale Divinity School. The fists followed us there. An older looking, long-haired hippie student in black motorcycle boots from Westville who rarely spoke but, when necessary, flashed a card referencing his black-belt karate credentials was our unofficial protector.

Then came the fire, soon followed by an even longer bus ride to Ridge Road and the cinder block classrooms of Congregation Mishkan Israel. We had a new principal – or should I say warden – for the balance of the academic year.

With the vacant lot as a catalyst, I wanted more information that might sharpen memories of the Sheridan Annex while helping me better understand its purpose and determine its fate. An April 16, 1995 headline and in the Connecticut section of the New York Times caught my eye – “Robert J. Schreck: Sponsoring Diversity in the Classroom.” The article was triggered by a Superior Court judge’s ruling on a lawsuit about racial divisions between Connecticut cities and their suburbs. Mr. Schreck had been an assistant principal at Sheridan and involved in the initial implementation of the Sheridan-Bassett pairing. He was also my principal at Lee High School.

I hadn’t communicated with Mr. Schreck since 1972, when I crossed the stage at Woolsey Hall to shake his hand and accept my diploma. I found his address and mailed a letter. A few days later, he called. We reminisced about Lee and talked about our children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. In response to my letter, he offered insight and anecdotes about the launching of the Sheridan-Bassett desegregation plan. I then asked about the Sheridan Annex. Was there anything he could share with me? Pausing briefly to calculate when he left Sheridan for Troup Junior High, he provided a succinct answer: “I had no idea it existed.”

Who created this experiment and what was its intended outcome? Is there a report somewhere, perhaps buried in the files of the New Haven Board of Education, that can provide some answers? What was Yale’s involvement, aside from making the Divinity School gym available to us? Did the mansion belong to Yale? Can any of my former classmates and teachers fill in some information gaps with their recollections?

Much has been written – nationally and locally — about New Haven’s public school desegregation plan. However, the story remains incomplete without including the long-forgotten Sheridan Annex experiment.

Arthur M. Horwitz was born and raised in New Haven and is a product of its public school system. He is a past chair of the Michigan Civil Rights Commission and Detroit Public Television/PBS-Detroit. A former reporter and bureau chief with the New Haven Register, he was inducted into the Michigan Journalism Hall of Fame in 2020. He resides in West Bloomfield, Michigan and can be reached at [email protected]

It is interesting to me that in 1963 that “Sheridan’s was 83.7% white.” By the time I entered Sheridan in 1977 it was 85-90% black students, and the students were divided into tracking levels based on supposed academic ability and almost no Hispanic students. The top two tracks were exclusively white, with track A students designated for Ivy League schools, track B was state college level, track C was community college or trade schools and was 75-80% black students, and group D was considered factory jobs level and high school dropouts at best and almost exclusively black students, and there was a very small group of special needs students who were being mainstreamed as an experiment.

I attended Beecher elementary where it was pretty evenly split between white, black and Hispanic students, with the only distinctions as to which class you were put in was if you couldn’t write in cursive. There was a huge amount of white flight between the 1960’s-1970’s.

I was put in track C due to my inability to memorize the timed tables, (my third grade teacher was a really intimidating and impatient teacher,) and my messy handwriting, even though I did very well with pre-algebra and geometry, and was reading 2-3 years above grade level.

Then my mother and Rhoda Spears of the TAG program fought to have me moved to track B. The only difference I could see between track B and track C students, that I could see, was the color of their skin, and some students in track B had an easier time sitting still quietly in class. But as far as I could tell, most students were getting b and c grades on most of their tests and homework, and the coursework wasn’t all that different. I quit the TAG program because I could see the work they were doing was the same work that my other classmates in track C were just as capable of handling, so I knew the tracking levels were simply based on cultural issues, racism, behavioral issues, and not on academic abilities.