Judging from the hoopla surrounding the world premiere of yet another Athol Fugard play in New Haven, Coming Home is about AIDS. But the play, which opened at Long Wharf Theatre Wednesday night, is really a different story — about the power of place, love, and storytelling to bind generations together.

Judging from the hoopla surrounding the world premiere of yet another Athol Fugard play in New Haven, Coming Home is about AIDS. But the play, which opened at Long Wharf Theatre Wednesday night, is really a different story — about the power of place, love, and storytelling to bind generations together.

Coming Home is the fourth world premiere to date in New Haven of the South African playwright’s work.

It is ostensibly about the ravages of AIDS in Thabo Mbeki’s post-apartheid South Africa. The scarcity of drugs and a health ministry that often believed more in superstitions than science doomed countless poor people to early death there, including Coming Home’s heroine, Veronica Jonkers.

When Veronica returns to her native ground, the dusty village of Nieu Bethesda in South Africa’s Karoo desert after the death of her grandfather, she has her 4‑year-old son Mannetjie in tow. She also bears certain knowledge she is going to die from the AIDS, which she has contracted when her aspirations to become a singer in Capetown crashed and led her to drinking and prostitution.

When Veronica returns to her native ground, the dusty village of Nieu Bethesda in South Africa’s Karoo desert after the death of her grandfather, she has her 4‑year-old son Mannetjie in tow. She also bears certain knowledge she is going to die from the AIDS, which she has contracted when her aspirations to become a singer in Capetown crashed and led her to drinking and prostitution.

Before she dies, she’s determined to secure her son’s future. She does this by invoking the stories of her growing up with her grandfather Oupa, his love of planting pumpkin seeds and farming the tough land.

But the real secret, and the key relationship that drives the play, is her determination to marry the illiterate, religious, charming Alfred Witbooi.

Whereas the clever Veronica’s aspired to be a singer, nerdily earnest Alfred has few ambitions but to own a red bicycle with a bell and horn and to ride proudly through town on it.

He loved her in the youth that they recount together; she cheated for him on school exams. But she was above him. Now, ironically, the disease Veronica returns with delivers her into Alfred’s metaphorical arms. Fearful that when she dies, Mannetjie will be taken by the authorities if the child has no father, she announces simply that he’ll marry her and become the child’s stepfather.

“What’s wrong?” she says to him after coughing up blood. “Your mother is dead and you’re too old and strange for any other woman to be interested in you.”

“What’s wrong?” she says to him after coughing up blood. “Your mother is dead and you’re too old and strange for any other woman to be interested in you.”

Coming Home has touching songs, especially the quietly powerful one Veronica has made up herself and sings to Alfred in the first act, about how he should not have second-hand dreams. There are also long stretches of soliloquies about the power of the land that engage often more poetically than dramatically.

Yet by far the most gripping feature of the play is Alfred’s transformation from witless friend to caring partner, to loving father of a next generation.

Long Wharf is making much of the AIDS material in Fugard’s play. But it feels far more as background to the Veronica-Alfred love story, which is played and paced with poignancy and a wisdom of the heart.

When Veronica tells Alfred what is ailing her, she cries, “Now you really are afraid of me. Go! Flee like they all do. You think you’ll catch it from my sneezing or if you touch the food I eat. Go.”

We expect Alfred to be overwhelmed or full of prejudice because he is a simple, very religious man. He surprises us with a maturity that his affection for Veronica informs. As she cycles through rage and self-loathing for what she has done to her son, he listens. She secures his commitment to tell the village that she has the flu.

When Alfred asks if there isn’t medicine, Veronica says yes, but it’s too expensive for the government to give to poor people. Instead, she says, “we must eat bananas and vitamins.” Somehow that’s more shocking to audience expectations, I think, than to the characters themselves. Yet, as always, Fugard’s dramatic tact and love for his character driven story allow him to touch the political or polemical, not be distracted by it.

Far more important is the treatment Veronica prescribes for Alfred to administer to Mannetjie: “Please tell him stories about Oupa, and please don’t let him forget me.”

Far more important is the treatment Veronica prescribes for Alfred to administer to Mannetjie: “Please tell him stories about Oupa, and please don’t let him forget me.”

Fugard has always written plays about ideas. But even in the ones most influential in the anti-apartheid era, such as Master Harold and the Boys, the ideas are presented through flesh-and-blood people who spar with each other, prodding, poking, and preserving their humanity against nearly impossible odds.

Likewise in Coming Home. Apart from comments by Veronica, such as “Capetown was made by the devil,” there is little by way of rant or rage or indictment of the South African government’s criminal slowness in rolling out retroviral drugs when they became widely available in the early years of the century.

Instead, as Veronica’s death is slowly accepted by son and new husband, the conflict that drives the second half of the play is how Alfred can overcome book-smart Mannetjie’s disdain for this man, whose simple goodness he has not yet come to appreciate. Veronica engineers it all, with the help of the spectral return of Oupa.

Fugard never rushes his story. He allows us to connect not only to the characters but to a social context for their lives.

In the first half of the first act, however, Veronica only has little Mannetjie to talk to, so that much exposition is conveyed in what feels like a soliloquy, which is brightened by her singing and theatricality.

The play impresses throughout by the power of simple dramaturgical means well deployed: a small number of characters and, in this case, a handkerchief held over Veronica’s face early in the first act that transforms her from grown woman to Oupa’s little granddaughter. When the old farmer then returns from the dead and tells her the story of her own birth, theater magic is on full display.

The play impresses throughout by the power of simple dramaturgical means well deployed: a small number of characters and, in this case, a handkerchief held over Veronica’s face early in the first act that transforms her from grown woman to Oupa’s little granddaughter. When the old farmer then returns from the dead and tells her the story of her own birth, theater magic is on full display.

The program describes Coming Home as Fugard’s companion piece to his 1995 play Valley Song, which revisits the same characters ten years later.

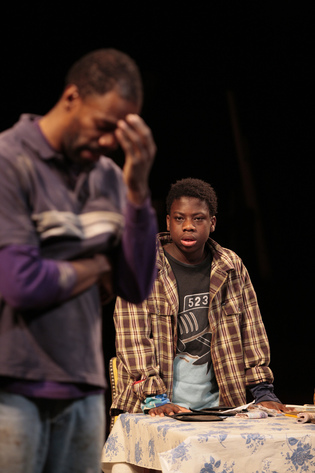

The actors are uniformly strong, with Roslyn Ruff as Veronica, Colman Domingo as Alfred, and Lou Ferguson as Oupa, with two young boys, Namumba Santos and Mel Eichler playing the younger and older Mannetjie. The set design features a windmill water pump on the left and farm implements on the right framing a shack with corrugated roof; it captures the soul-sapping poverty of rural South Africa. It was informed by a journey director Gordon Edelstein and his team took to visit the Karoo.

Programming in connection with Coming Home includes a food drive to benefit AIDS Project New Haven; a symposium on the healing power of art, “Global Health and the Arts,” to be held Thursday at 3:30. For other programming and tickets, contact the Long Wharf Theater at 787‑4282 or longwharf.org. Coming Home runs through Feb. 8.