Maya McFadden file photo

At this year's final eighth-grade promotion ceremony at Wexler-Grant, in June.

Allan Appel file photo

Dixwell Alder Jeannette Morrison (right), with the late former Wexler-Grant Principal Jeffie Frazier, in 2019: "There is a rumor [Wexler-Grant's] closing, but that's not true. That's why I'm not sad. It's being repurposed for a specific type of learning and it'll provide the children and parents in the district with a new option."

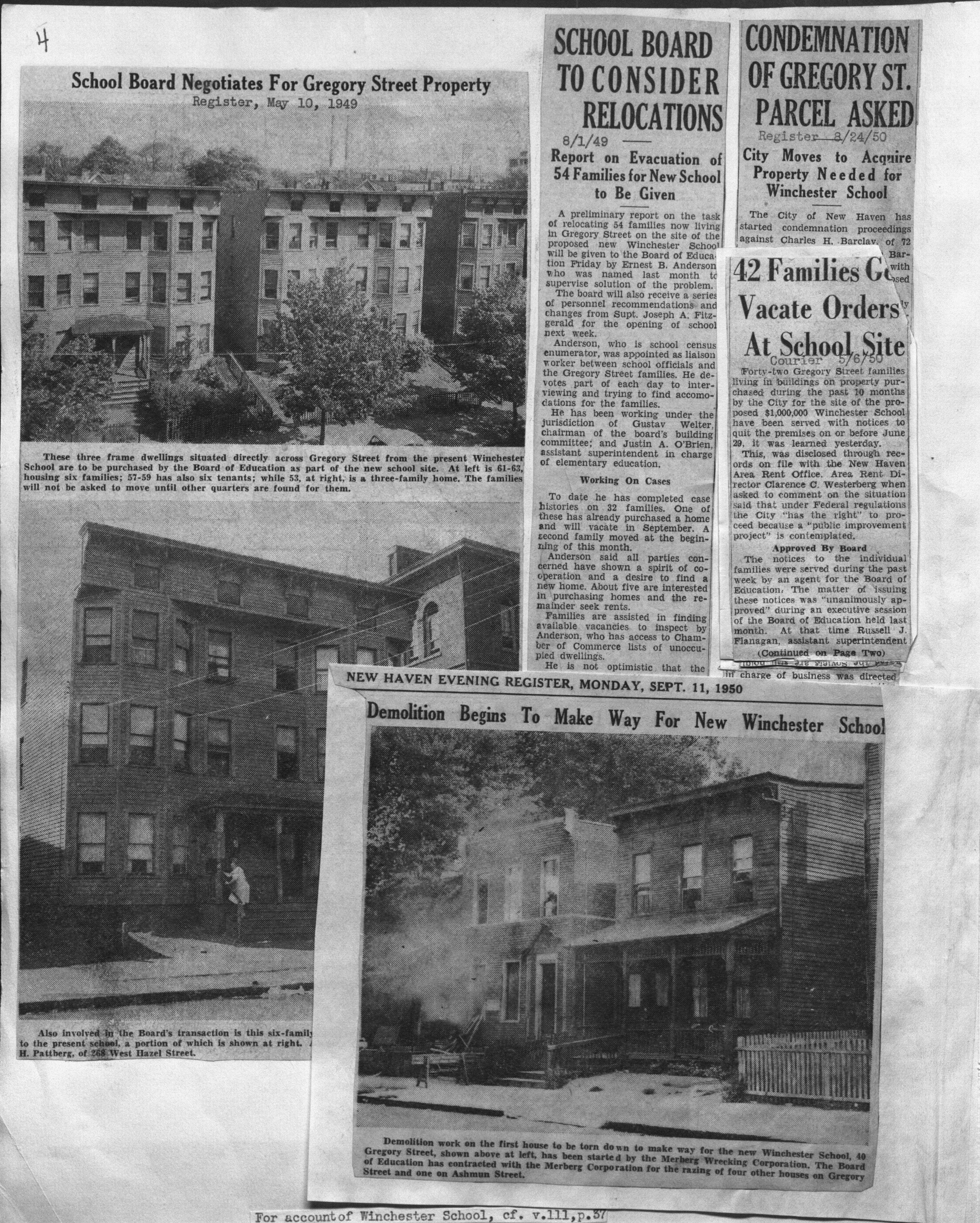

From the archives: Winchester Community School rises.

As Wexler-Grant prepares to merge with Lincoln-Bassett, this reporter took a step back into the Dixwell school’s long history as a pioneer in the movement to make room for kids, parents, and community alike.

Wexler-Grant, a K‑8 school at 55 Foote St., will be leaving its longtime Dixwell neighborhood home this fall, as the school is merged with Lincoln-Bassett School in Newhallville.

The imminent loss of Wexler-Grant is largely due to declining enrollment. That has been the case across the New Haven Public Schools (NHPS) district since about 2017, and is also the primary reason why the superintendent will be closing Brennan-Rogers School in West Rock.

While nothing is certain as the Board of Ed struggles with perennial budget gaps, the Wexler-Grant building is scheduled to remain at 55 Foote St., and will become the site of an experiential learning-based middle school, with an incoming first cohort of 30 sixth-grade students this fall.

Nevertheless, this shift is a big deal.

For it’s even more than the disappearance of a fully functioning neighborhood school; it’s the loss of a school that embodies the names of pioneering anchors of the community school concept in New Haven, Isadore Wexler and Helene Grant.

Wexler-Grant — and especially its predecessor, the Winchester Community School — was also one of the hubs, along with the Q House, of the old Elm Haven neighborhood out of which so many of today’s New Haven elders have sprung.

So it’s a watershed moment, especially for the Dixwell community, that deserves a looking at.

To do that, this reporter did some time-traveling through past files of the New Haven Register, the Independent, the archives of the Jewish Historical Society of Greater New Haven, publications of the Ethnic Heritage Society, records of the Connecticut State Department of Education, and general history sources online. This article also features interviews with former Winchester School students, the neighborhood’s current alder, the city’s former mayor, and other key players in the city’s changing school district over the years.

With an eye to the school change in New Haven that is happening now, here, more or less, is what happened then.

Winchester Community School

Photo provided by Sherell Nesmith

Sherell Nesmith: "I was in the band, there was rocket club for the boys, ballet classes, annual square dancing, every activity you could think of."

Wexler-Grant, previously named the Isadore Wexler Community School, was the direct descendant of the Winchester School.

That school was built in 1952 on the spacious right angle lot between Dixwell Avenue and Foote Street behind the Q House and deep in the heart of the Elm Haven “projects” (now Monterey Place), which had gone up in 1941, and whose residents it was primarily designed to serve.

Winchester was the flagship school of the “community schools” movement, a kind of first in New Haven.

Its founding principal was Isadore Wexler, a Columbia Teachers College-educated pioneer of the community school movement. The full name was Winchester Community School — and the original pile of bricks that it was itself replacing stood on nearby Gregory Street, but by the late 1940s had outgrown its space.

The community school idea was a simple one — to transform a school that was previously just for kids to one that could equally serve their parents and community. It included new spaces, like multi-service rooms and well equipped cafeterias and after school enrichment programs galore where adults might come for a class in the evening or weekend. It helped foster the creation of the city’s first Parent-Teacher Association (PTA), and provided space for block watches to meet and organize.

Even though many of the programs might not have been funded by an at-times skeptical New Haven Board of Ed, Yale University social justice pioneers, social service agencies, and other local partners that Wexler and his colleagues in the African American community could bring in, along with their volunteers and resources, could fill the gaps.

And the whole ambitious thing was fueled by generous Model City national war-on-poverty federal funding that poured into the Dixwell community in the 1950s and 1960s largely under the leadership, and pressure, of Mayor Richard Lee.

The concept of a school with doors that are open from early morning often to ten at night, and where there were activities on the weekend and even holidays, and there were enrichment classes in photography and organized trips everywhere, all took immediate root among the residents of Dixwell’s High Rise/Low Rise apartment buildings, as the buildings of Elm Haven were known.

Many students at Winchester, like Samantha Myers-Galberth and Sherell Nesmith, were self-described latch-key kids, and among many from single-parent family homes where the parent worked late and odd hours.

In many ways the community schools idea is a no-brainer. Over the decades it has evolved in many forms. Well-meaning officials in different waves of funding and research have tried to address the kinds of wrap-around services for a school, which are needed to lend people that extra resource to overcome economic insecurity and poverty because those were seen as serious obstacles to education.

When the Conte School on Chapel Street was opened in 1962, that signaled the formal adoption by the Board of Ed of the community school concept and a dozen others followed, with the concept being tweaked and evolved.

Prior to Conte, Winchester was the first community school in the city and perhaps New England to be built — that is, with an eye to the kinds of rooms, spaces, services, and general design that might serve not just children but the kids’ community

Click here, for example, for an article about a recent latter-day edition of the community school concept as it has developed in Fair Haven since 2024. And click here for an article on the naming of New Haven’s schools after our educators, including Isadore Wexler, Helene Grant, Reginald Mayo.

Yet back in 1952, with Wexler at the helm and with buy-in from Dixwell business, political, and church leaders, the concept, powered by infusions of federal money, overcame objections from the Board of Ed.

The school — with a proposed 690-student capacity, and at a cost of $1,054,000, and Wexler as its inaugural principal — opened in 1952. Wexler stayed as its principal for 17 years until he moved into Board of Ed administration.

“It was like a city within a city,” Nesmith said about the busy informal campus comprised of the Elm Haven High and Low rises, Q House, Stetson Library, and the Winchester School.

“Dr. Herman [the principal at Winchester Community School after Wexler, who stayed in the post for 11 years] allowed the building to be open seven days a week, even on the weekend … I was in every school program. Living in the projects, most of us were latch-key kids, most had one parent. I was in the band, there was rocket club for the boys, ballet classes, annual square dancing, every activity you could think of. Like a Mecca for us.”

Nesmith, who spent third to sixth grade at the Winchester School from 1969 to 1972 when her family moved to Dixwell from the Hill, is the unofficial historian of the area and especially of the Winchester School and its successor that opened on the site in 1987. For many years, she has worked at Yale New Haven Hospital.

"The Doors Of A Community School Never Close For A Season"

Maya McFadden photo

Sara Wexler, granddaughter of school's namesake Isadore Wexler, giving a keynote speech at this June's final graduation ceremony for Wexler-Grant: Isadore Wexler was "a man who was ahead of his time."

The original Winchester School — named after Oliver Winchester, who founded the gun factory in New Haven in 1866 — was on Gregory Street on the north side of the complex, and Isadore Wexler had become principal in 1946.

An athlete himself and the operator of a summer camp, Wexler was an evangelist for the community school concept. As such he pioneered establishing the city’s first PTA at Winchester in 1948. In the new building, constructed at 209 Dixwell Ave. in 1952, he set up an expansive gymnasium with bleachers, the first hot lunch program for any public school in Connecticut, and — another first — a serious 9,000-book library designed to be used both by the school and community members, and it was officially dedicated by Mayor Lee in 1960.

The menu of after-school programs kept growing to include Scouts and Brownies, serious home economics, and the Benjamin Banneker Advancement Academy for the bright fifth and sixth graders that taught literature, creative writing, and French. There was also a rocket club so the Elm Haven kids could help the country catch up to the Russians in space.

“Everyone walked to school,” recalled Samantha Myers-Galberth, who attended Winchester between 1970 and 1976. “We all knew each other from the high rises and low rises. We got out at 2:30, then after school until 6:30. You would go home and come back to the gym, trampoline, basketball, and you could go over to the Q House.

“And Dr. Herman was always around. He had us in a way that we wanted to please him to be happy with our success. So friendly and yet also stern. He was an advocate for making you feel better about yourself.”

Whatever the community needed, it seemed, some program in the school, staffed both by Yalies and other volunteers and neighborhood nonprofits, tried to address. A 1973 article in the New Haven Register by Harold Hornstein reads, “School vacation programs and the doors of a community school never close for a season. Vacation programs include sports, camping, summer school, story-telling, many recreational activities, and a tiny tot program.”

Wexler and later Herman along with a Dixwell Community Council made the case for all kinds of continuing education for mothers, and related programs that addressed food and shelter needs as well of the Elm Haven families. And when the Board of Ed balked at the funding, the proponents of the community school found the dollars elsewhere in the community.

When I interviewed them, both Myers-Galberth and Nesmith told stories of a pantheon of memorable teachers who staffed Winchester, including many African American teachers. Chief among them, if only four-foot-eleven, was Ms. Sylvia Hare, the gym teacher who taught them square dancing (it teaches you timing and unity and how to work together!), and who also had the highly authoritative “stare” that kids knew from their parents meant, “Now is the time to behave, or else.”

“I had a Ms. Foster in the fourth grade,” recalled Myers-Galberth, who this year is celebrating 30 years of her hair styling business, now headquartered in Westville. “She called my mom and asked if she could teach me about plants, and she took me all over, to East Rock, and I still love plants and flowers. The teachers really knew and cared for us, they were really into the students individually.”

One of those teachers, Helene Grant, had been an early colleague of Wexler’s at Winchester and had been teaching in the New Haven school system since 1919; she was the third African American teacher in the system, and both she and Wexler were destined to have schools named after them, but not without some controversy.

Over the years after they were torn down in 1991, the “boys and girls” of the Elm Haven projects have organized reunions. At one, they specifically brought back Ms. Hare who had retired in Texas. Nesmith, who recalled this gym teacher, said she was in effect an assistant principal in her authority, had an office adjacent to the gym, and the students dreaded to be called in there.

At one reunion, with a smiling, tiny, perhaps less daunting and now grey-haired Ms. Hare nearby, Nesmith and her friends practiced “the stare” and expressed their love that, by all accounts, embraced teachers like Ms. Hare along with the culture they helped to create not only in the school building but the surrounding community.

Barbara Tinney, who went on to a distinguished career in social work in New Haven, recollected the quality of the teachers at Winchester and the general atmosphere of pride and self-sufficiency that, despite problems of economic insecurity and poverty, were obtained in the Black community.

She estimated that half of the African American teachers in the entire New Haven school system at the time taught at Winchester.

“Winchester,” she said, “defied the terms now used to label the experience of African American children in New Haven — disadvantaged and traumatized.”

In its heyday the Winchester school had about four classes per grade, recalled Myers-Galberth, which added up to a total of some 600 students, which was more than capacity for the 1952 building and a lot for an elementary school.

What's In A Name?

Thomas Breen photos

Adieu, Wexler-Grant.

Despite the continuing inflow of federal money, however, the new housing and even the new commercial initiatives that made up Dixwell Plaza across from Winchester School began to struggle. Later acknowledged to be caused in part by insufficient local input in the planning, the area’s unemployment and other problems began to lead to an exodus from the area. Dixwell’s population in 1960 was 10,229 and in 1970, 7,200. That trend persisted into the 1980s.

The current Wexler-Grant building was preceded on the site by the Isadore Wexler Community School.

The Isadore Wexler Community School, in turn, opened in 1987 as the successor to the original 1952 Winchester School building.

In the late 1990s, under the School Construction Program of the DeStefano administration, it was renovated and inaugurated in 2004.

In 2004, the school re-opened with 522 students, according to Connecticut Department of Education documents. In a continuing echo of the community school concept, parents were urged to contribute 20 hours a semester volunteering at the school in activities outside of their child’s classroom. There was a family resource center and a lot of attention to grandparents and what the school could do to help them raise their kids’ kids, like learning computers.

The school by then was also a Comer model school with a focus on early childhood education.

The plan was to reopen in partnership with another school and extend up to the eighth grade.

Back in 1964, before the serious racial unrest of 1967, and with a growing population of kids, another school was optimistically built nearby on Goffe Street in honor of Helene W. Grant.

She had taught at the Winchester School for 42 years, had been a colleague of Isadore Wexler, and became the first African American woman after whom a school was named in New Haven. The school, built on the site of cleared residential lots in Dixwell as part of the continuing Urban Renewal efforts, remained until 2014, when it was replaced by the Reginald Mayo Early Learning Center.

“Depending on where you lived,” recalled Myers-Galberth, that is in which of Elm Haven’s five buildings, you would start at Helene Grant, which went only to fourth grade, or at Winchester.

In 1966, Jeffie Frazier came to New Haven from Louisiana and became a teacher at the new school. She went on to become a Fulbright scholar, principal of Helene W. Grant School and a civic and community leader. In a spirit not unlike Wexler’s, she overcame Board of Ed objections and became known, among other things, for instituting dress codes — a first in the public schools of the state — in order to reduce tension among the kids. She organized trips to Senegal, among other locations, and instituted the singing of the African American national anthem in the school to boost self-esteem, and she was known as an activist educator/visitor in the homes of many of her students.

These achievements were recalled in 2019 when her students and other admirers, many grown to become social workers, police officers, teachers, and even principals themselves, organized to name the Foote Street entryway to the Wexler-Grant School “Jeffie Frazier Way.”

After 35 years of teaching in New Haven, Frazier’s last post, before her retirement in 2008, was as principal of the by-then combined Wexler-Grant School. Frazier died in 2021.

In an autobiographical statement she wrote to family, friends, and admirers before she died, Frazier reflected on her career this way: “I was on the battlefield for justice, truth, and education for the youth of the urban schools in Connecticut. Children must feel good about themselves before they can feel good about the world in which they live. … I dreamed and it became a reality for my school. Helene Grant was a public school with a private school mentality. Everything, and I mean everything, was within our reach.”

That’s another way of speaking about the community school movement.

We can’t quite close this tale — a kind of swan song to the Wexler-Grant School — without trying to bring clarity to how Wexler-Grant got to be called Wexler-Grant. And here my sources are a little murky.

To that end it’s instructive to try to return to the mid-1980s, by which time Isadore Wexler, after having been principal of Winchester for 17 years, was an administrator in the NHPS system supervising the career and work study programs. His protégé Dr. Barry Herman, who had been principal for 11, was also an administrator, and the Helene Grant School was operating nearby on Goffe Street.

It was time, yet again, in 1982, after some 30 years of use, to rebuild or renovate the Winchester Community School building.

Articles in the New Haven Register indicate that in order to perform the work, Winchester School may have been vacated, with students transferred temporarily to Helene Grant or other schools. Now it was time to move back in to the renovated building with a new wing facing Foote Street, and a name change was in the offing.

The Board of Ed proposed as the official name the Isadore Wexler Community School as an appropriate memorial to Wexler, who had been principal of Winchester from 1952 until 1969 and had served, all told, 58 years, as an educator in New Haven. Mayor Ben DiLieto had approved.

A committee was formed to come up with the right name, but oh those committees!

When the Wexler name was proposed, the Dixwell Community Council objected. Or some portion of the community did. They, members of the PTA, and others wrote that the community had not been consulted sufficiently. Someone is quoted, anonymously, in a Register article as writing, “Wexler had no connection or experience with the Black community, and we want the name changed back because the name of the school has great sentimental value to people in the community.”

Dr. Herman is quoted as riposting that then, by 1984, by which time recriminations were already flying about the failures of Urban Renewal in Dixwell, it was a shame that most of those who had known the role Wexler had played in the community school movement were no longer around to testify on his behalf.

In any event, the mayor and Board of Ed insisted on memorializing Wexler, and the school opened officially as the Isadore Wexler Community School.

John DeStefano, who did not become mayor until 1994, was a high-level administrator in the 1980s, and said in an interview that he remembered no sturm und drang connected to the school naming, no real controversy.

The “Grant” name was added to Wexler, he recalled, when the Helene Grant School was torn down, “and we wanted to keep it [the name] in the neighborhood. We would have school-based management teams and the consensus was to join the names. We did that with one other school … with Mauro-Sheridan, as part of rebuilding the school infrastructure.”

Susan Whetstone, who worked as an administrator and chief of staff with DeStefano during those years, wrote in an email: “My recollection is that when we renovated the [Wexler] school under the School Construction Program in about 1994, we combined Wexler and Helene Grant as part of a K‑8 consolidation. At the time there was an idea to turn the Helene Grant building into a pre-school program.”

And Susan Weisselberg, who helmed the School Construction Program in those years, confirmed: “The principal of Helene Grant, Jeffie Frazier, became the principal of the combined school. The old Grant school was first used as swing space for various schools and then demolished, with the site becoming the home of the new Reginald Mayo Early Childhood Center, which opened in 2015.”

About the community school movement in general, which DeStefano formally tried to revive in 2006, the former mayor added that the two other points of development that under-girded and advanced the concept included incorporating air conditioning (and features like the pool at Conte Community School) in all the schools. That enabled buildings to serve the whole community, especially in the summer.

“Conte was the epitome of that, including the addition, with Dr. Comer, of adding early learning, that was a big extension” of the community school concept, he added.

The current focus “is to right-size buildings for student enrollment,” DeStefano said. “The larger question is why school enrollment is declining when the population [of the city] is growing. But that’s another issue.”

“About the merger, I have no words.” said Sherell Nesmith, sadly, about Wexler-Grant merging with Lincoln-Bassett.

“In the 1970s those teachers were like surrogate parents. They used to take us home on weekends, and we met their kids. I spoke at the funeral of one of my fourth grade teachers because those were the kinds of relationships built. Though they added an addition, it will always be Winchester. It’s a great loss and a void.”

Yet Ward 22 Alder Jeanette Morrison disagrees, and emphatically. “There is a rumor it’s closing, but that’s not true,” she said about the Wexler-Grant building. “That’s why I’m not sad. It’s being repurposed for a specific type of [experiential] learning and it’ll provide the children and parents in the district with a new option.

“I have to give the district kudos. They did their homework. The majority of kids at Wexler-Grant do not live in my ward,” she continued. “The percentage from Ward 22 is very low. They have 14 or more buses who come from all over the city. As far as the families in my ward being affected, I haven’t received any calls.”

Morrison recalled that she went to school at Newhallville’s former Jackie Robinson School, where at least aspects of the experiential learning model scheduled to be instituted at Wexler-Grant in the fall were already in full swing. “We had home economics, cooking, sewing, ceramics, hands-on stuff,” which were ideal, she said, for someone like herself, a tactile learner.

“If you’re doing something new, this — Wexler-Grant and the Dixwell neighborhood — is the place to do it,” Morrison added. “You’ve got the Q House, ConnCAT coming on line with all these different stores and services where kids can explore all kinds of jobs, the church, all these on the same block, and getting them to start to think about their next steps. It’ll be a great partnership.”

Readers are encouraged to correct errors and especially to fill in the blanks of the history in the comments section below. When a beloved school like Winchester/Wexler-Grant merges or disappears and with it such memories, the more — and the more accurate — the history we can muster together the better.