Thomas Breen file photo

Judge Papastavros: Alders' right to sue "inherent in its legal duties."

A state judge has ruled that the Board of Alders is legally allowed to sue the City of New Haven.

The landmark separation-of-powers decision means that a lawsuit first filed five years ago — and that centers on a dispute over former fire union President Frank Ricci’s pension — is one big step closer to going to trial.

Such is the latest with Board of Alders v. City of New Haven.

The case itself dates back to July 2020, when the alders first filed suit over Mayor Justin Elicker’s approval of a $386,659 pension enhancement for Ricci.

The Board of Alders has argued that the city’s payment of this annuity violates a local law that requires all contracts worth at least $100,000 to first be approved by the city’s legislature. The mayor has responded that the city was legally required to make the extra retirement payments because of a memorandum of understanding (MOU) first signed in 2006 between the DeStefano administration and the fire union, then amended in 2019 by the Harp administration to specifically provide for Ricci.

Last Thursday, state Superior Court Judge Angelica N. Papastavros issued a 12-page ruling that denied a May 2 motion to dismiss filed by Ricci and his wife Christine. (While the City of New Haven is the main defendant in the case, the Riccis — as the beneficiaries of the disputed pension enhancement — are also listed as defendants.)

Papastavros’s decision doesn’t concern the substantive matter of Ricci’s pension bump. Instead, it answers the question of whether or not the city can sue itself.

In this case, that answer is yes.

In her ruling, which can be read in full here, the judge made two key findings on a legal question with little state-court precedent as she cleared the way for the alders to move forward with their lawsuit against the Elicker administration.

First, she found that the Board of Alders is a distinct “body politic” from the mayor and the rest of city government. As the city’s legislature, it’s essentially a separate branch from — rather than a division of — the executive branch of municipal government.

“Given its status as the city’s legislative body, and the fact that it is a required entity under state law, the plaintiff certainly qualifies as a separate body politic from the mayor and the rest of city government,” Papastavros wrote. “This fact supports the conclusion that the plaintiff has standing to sue.”

Second, the judge found that the city charter grants the alders the right to file lawsuits to enforce local laws, even if that power is not clearly spelled out in state law. She pointed in particular to Article IV, Section 4(A) of the charter, which reads in relevant part that the alders have the authority “to prescribe the manner of enforcing the penalties for violation of Ordinances enumerated in the foregoing sections … by a civil action or forthwith process as in criminal cases.”

“The quoted language in the city’s charter certainly suggests that the plaintiff would have the authority to bring a lawsuit in order to enforce its legal rights and obligations under that document,” Papastavros wrote. “Accordingly, the court concludes that even though there may not be direct statutory authority authorizing a Board of Alders such as the plaintiff to initiate a lawsuit, such power is inherent in its legal duties and responsibilities.”

This case had been set to go to trial in May — until the Riccis filed a motion to dismiss on the grounds that the Board of Alders is a part of the City of New Haven, and the city can’t legally sue itself.

In a Church Street courtroom earlier this month, attorneys for the Riccis and for the Elicker administration urged the judge to throw out the five-years-and-counting court case on that very jurisdictional question. They argued that the Board of Alders is the “legislative arm” of municipal government, but that it is not a “distinct body politic” or separate legal entity, and therefore cannot file lawsuits.

Jonathan Einhorn — a local attorney and former alder who, along with fellow former alder and lawyer Steve Mednick, has been representing the Board of Alders in this case — called on the judge to let the case continue. He said that of course the Board of Alders, as the city’s legislature, is legally allowed to file lawsuits to enforce local laws. Otherwise a separate, co-equal branch of city government would be rendered essentially powerless in the face of a law-breaking executive.

In a July 17 brief in support of his position, Einhorn accused the Elicker administration and the Riccis of advancing “a local version of the unitary executive, which finds currency in certain political circles in Washington, D.C.”

He wrote that such a conclusion would “leave the lawmakers of the municipality at the mercy of the executive and would create an imbalance that undermines the ability of the legislative body to represent the people who elected them to office.”

He continued: “If the position of the Defendants were to be accepted by the court the question for policymakers throughout the State of Connecticut would be: how do we resolve a conflict where an errant Mayor defies the charter or subverts the ordinances? Is the answer to the question ‘raw politics’ or utilizing ‘removal’ provisions (if that municipality has a special act provision to that effect) or duels on the town green? The elected legislative representative as a matter of logic and law should be able to call on the civil justice system for equitable or legal remedy as the Plaintiff has done in the instant case.”

In a July 16 brief submitted in support of the Riccis’ motion to dismiss, Elicker administration-hired attorney Paula Anthony called on the judge to throw out the case on the same grounds that the Riccis argued — that the alders don’t have standing to sue because they are a part of city government.

“The Board of Alders, as the legislative body of the City of New Haven, is without authority to sue and be sued as a legal entity separate and distinct from the City of New Haven,” Anthony wrote. “The Board has failed to establish that it otherwise has the authority, independent of the City, to sue or be sued. The Board’s incapacity deprives this Court of subject matter jurisdiction. The Board’s conclusory statements that this issue is a ‘no-brainer’ are no more than a phantom argument and simply insufficient to meet its burden to prove standing to bring this action.”

Ultimately, Papastavros sided with Einhorn’s and the alders’ argument.

With so little case law in Connecticut bolstering a city legislature’s bid to sue its executive branch, the judge looked to state court decisions in New Jersey and Pennsylvania for support.

She referenced a 1989 decision by a New Jersey’s appellate court, which ruled that the Newark City Council had standing to sue the city’s mayor in “an intragovernmental dispute regarding which branch of city government had the authority to determine which parcels of city-owned land could be sold at public auction.”

She also referenced a 1993 decision by a Pennsylvania appellate court, which found that Pittsburgh’s city council had standing to sue the city over the location of fire stations.

Returning to the New Haven-focused case before her, Papastavros wrote that, “if the plaintiffs’ allegations are proven to be true at trial” — that is, if the mayor did indeed violate local law by approving Ricci’s pension enhancement — “but the plaintiff were not allowed to bring this lawsuit, it is entirely possible that the plaintiff and city’s taxpayers would be without a legal remedy to challenge the alleged ultra vires acts committed by the city and its mayor. Accordingly, the plaintiff has standing to bring this lawsuit.”

Papastavros’ decision — a major win for the alders and for their lead attorney in this case, Jonathan Einhorn — happened to come down on the same day that Einhorn agreed to give up his law license.

Per a press release from the U.S. Attorney’s Office of the District of Rhode Island, Einhorn has signed a deferred prosecution agreement after federal prosecutors “independently developed evidence upon which a jury could find beyond a reasonable doubt” that, in May 2023, he smuggled paperwork stained with synthetic cannabinoids into a Rhode Island prison.

As of Monday, Einhorn — who represented Westville’s Ward 25 on the Board of Alders for 16 years through 1991 — is still listed as one of the attorneys representing the alders in this case.

Mednick: A Win For Separation Of Powers

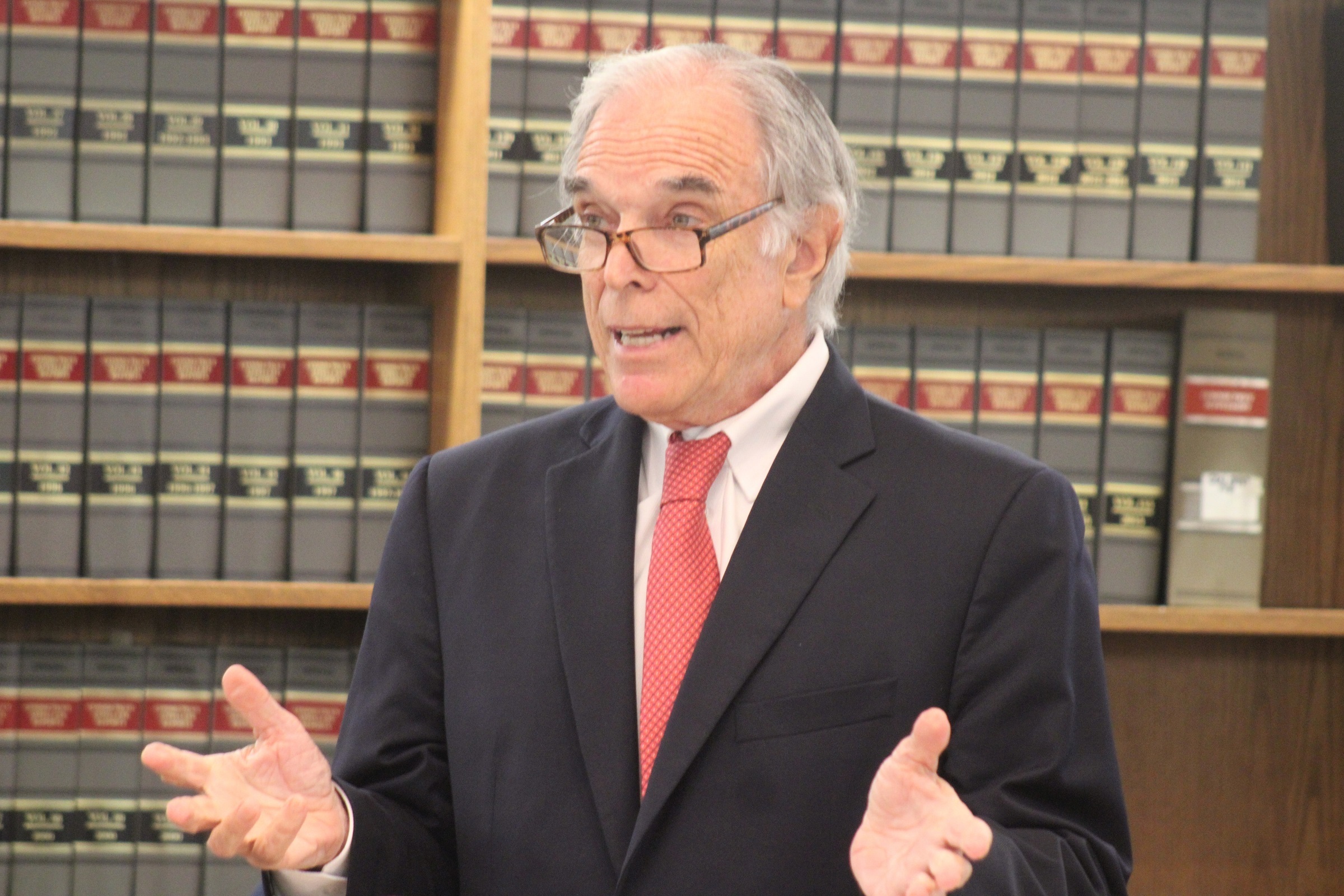

Thomas Breen file photo

Board of Alders attorney Steve Mednick.

Steve Mednick — who in addition to being a former alder served as the city’s corporation counsel in the 1990s, and currently works across Connecticut as a city charter expert – said that he and the Board of Alders are now looking for a new co-counsel to help litigate this case.

“I am not primarily a litigator,” Mednick said during an interview on Monday. “I’m here mainly because I represent the Board of Alders, and I do a lot of work on home rule.”

Medick said he hopes to find a new co-counsel for this case by this week. The judge hasn’t set a new trial date yet, but trial could be imminent, given that this case was all set to go to trial in May before the Riccis filed their last-minute motion to dismiss.

Mednick also heralded the judge’s decision as a key win for the separation of powers at the municipal governmental level.

“The judge recognized that, while local governments are not a sovereignty — we’re municipal corporations — that the state law of home rule recognizes the separation of an executive branch and a legislative function,” Mednick said, “and that for a legislative body to coexist with an executive that is a full-time employee of a municipality, they need to able to assert their rights in order to protect the laws adopted by the legislature and signed into law by the mayor.”

In a separate interview Monday, Mayor Elicker acknowledged the judge’s decision, and stressed that the motion to dismiss was filed by the Riccis and that the city had filed a brief in support at the request of the judge.

He also said that he is bound by the charter to fulfill the obligations of the previous agreements that resulted in the pension bump. He said this decision presents the alders and the city with an opportunity to settle the case, though he’s not sure if the two sides will be able to reach such an agreement in order to avoid going to trial.

Thomas Breen photo

Alders' attorney Jonathan Einhorn ...

... and Riccis' attorney Eric Brown, and city attorney Paul Anthony, in court on July 14.