Leila Daw

Beech Leaf Disease (detail).

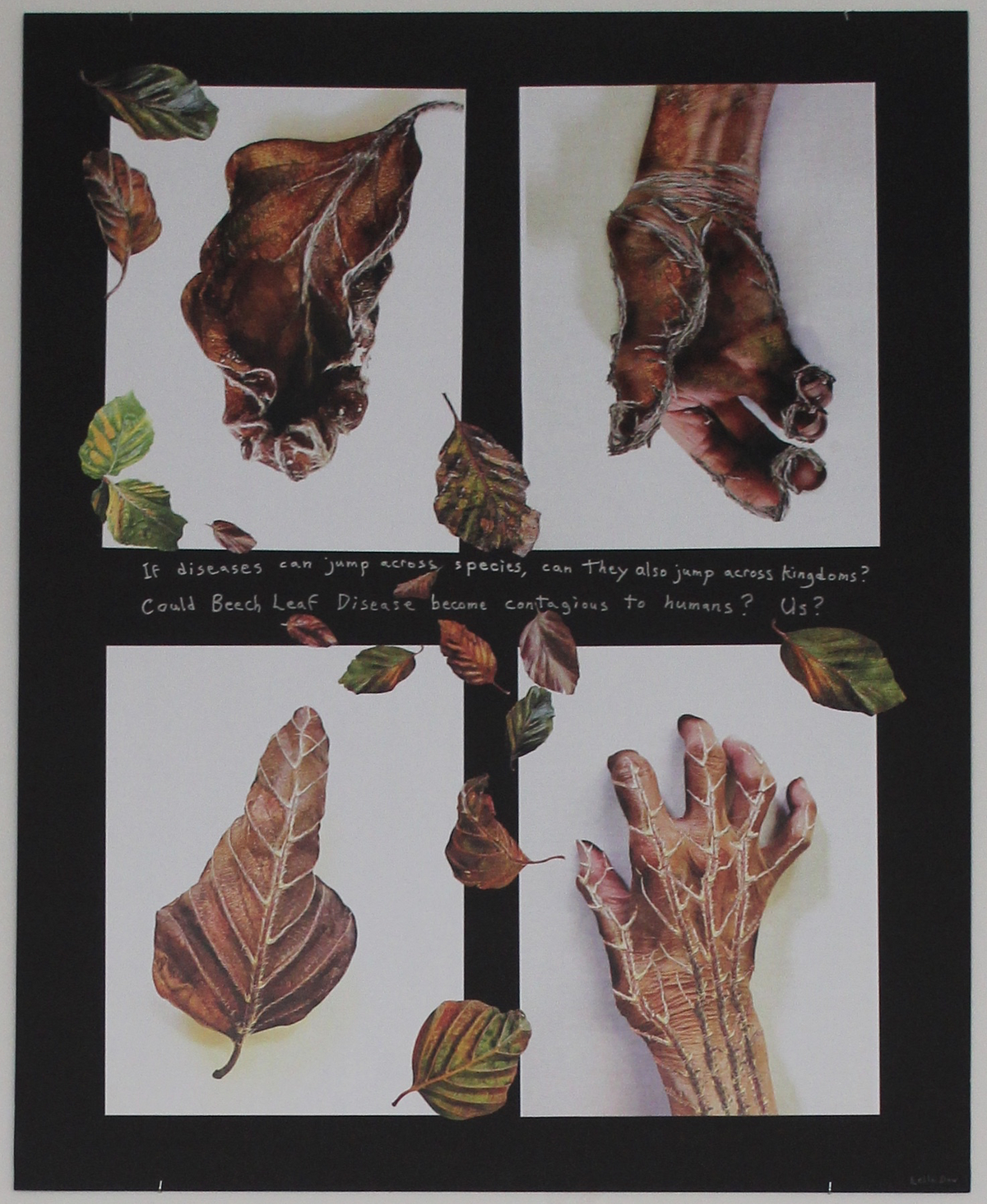

Leila Daw’s Beech Leaf Disease may be a work in progress, but in its assemblage it packs a powerful punch.

The first element is a collection of dried beech leaves; presented as art objects, we get to contemplate their form, which is important for what follows. First there’s information from the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station about beech leaf disease, which puts the leaves in context. They’re not the result of seasonal change, but of illness, and an illness exacerbated by climate change. But the top panel asks a compelling question: “If diseases can jump across species, can they also jump across kingdoms? Could beech leaf disease become contagious to humans? Us?” Thus the picture of human hands changed as beech leaves are. It’s an idea straight out of a good science fiction movie, troubling and at the same time possessed of an eerie beauty. Would beech leaf disease in humans be devastating? Or transformative? Or both?

Daw’s piece, drawing inspiration from a variety of environmental themes, is part of “Waste Management: Reuse, Reimagine, Repurpose,” organized by Rashmi Talpade and Martha Willette Lewis, and on view now at the upstairs gallery at the Institute Library through January 2023. The show is of “collages and assemblages made in response to the climate crisis,” as an accompanying statement reads. “It fills our gallery with objects, images, and poetry, addressing our world, our relationship to waste, consumerism, nature and our place in the ecosystem. Sourced through an open call, this inclusive show features the work of 37 artists from ages ranging from 6 to 86, offering visual meditations, commentary, and responses to the current situation.

Sarah Schneiderman

Triggered by Trash in the Ocean (Pinktail Triggerfish).

The inspiration behind the show is obvious; climate change is “the overriding cause that’s going to drive social justice, inequalities, and all of our survival priorities, starting now,” and for the forseeable future, said Lewis. “Collage and assemblage are perfectly suited to, even unconsciously, critiquing the system.” Beyond the simple fact of usually reusing materials, the subjects those materials evoke have meaning. “If you’re using advertising material, you’re using things that have all kinds of ideas about race and plenty and gender and capitalism,” and the idea of “enough, and what our priorities are, and what a good life is. That gets oddly and easily built into all of the work.”

Talpade and Lewis (l. and r.) with Scott Schuldt's Huldra.

Talpade and Lewis have known each other for years and are mutual admirers of one another’s work. “I’ve been doing a lot of collage projects,” Talpade said. “That’s my main subject. So when she mentioned doing a collage show, I said, ‘yes! let’s do it!’ ” Talpade’s collages in the show are made from photos she took of “waste and urban decay — all the abandoned buildings,” things which “I find extremely fascinating. I grew up in Bombay, which is one of the most complicated, messy cities in the world. It has just grown over the decades so there is no segregation of neighborhoods. There is the old industrial mixed with modern, fancy apartments. It’s all on top of each other. So, somehow my mind processes everything I see that way. In all the shiny buildings I see something that is … less than perfect.”

Rashmi Talpade

Urban Legend 2.

Talpade and Lewis also highlighted that there is something very democratic about collage. “The moment you say ‘collage,’ people say, ‘oh, I did that in kindergarten,’ ” Talpade said. “They know what to do,” Lewis added. “ ‘I’m not an artist, but I do collage,’ ” Talpade continued. “I’ve heard it so many times.” But “that makes me happy, to hear about people making art without feeling like they’re under pressure — there’s nothing like it.”

Linda Cardillo

Reflections.

Making art about environmental issues also puts into focus the materials being used to make that art, and the way artists use those materials in creating their pieces. In collage and assemblage, “you’re reacting to things that already exist, that have age and patina on them usually. They have a kind of character. So you’re working with your materials in a different way.” Found objects aren’t a blank canvas. And on a deeper level — at least now, in the modern era — turning to collage and assemblage highlights “our disconnect with materials” no matter what kind of art one is making.

Today, Lewis pointed out, the materials most artists use to make art are themselves products, usually of industrial processes. “In the past, artists ground their own paint, and they were made out of things from the earth that got burned or chemically processed,” she said. Artists used to have to collect wax and clay; “You got clay from the earth and refined it, getting all the pebbles and other things out.” But “now you just buy this stuff.” Paint and clay are manufactured. Machines used to make, say, stencils, are made of plastic, as are the sheets that stencils are cut from. If artists are making art about the environment, is it possible to create that art in a more sustainable way?

The question, to Lewis, seemed especially timely given her perceiving increase in the number of people — “people who aren’t necessarily calling themselves artists” — getting into making art and crafting, in part due to the pandemic, in parallel with a documented rise in climate anxiety.

“I wanted something to get people to go a little further than just worrying about it,” Lewis said. “Maybe look at what you could actually do.” To that end, the exhibition has partnered with Reimagining New Haven in the Era of Climate Change; Talpade and Lewis are working up a collage workshop for that organization’s climathon event on Oct. 29. It is also working with Ecoworks, which describes itself as a “thrift store for art supplies”; Talpade and Lewis are planning a tour of Ecoworks for interested artists and are going to have some Ecoworks supplies on hand. They are working with the Institute Library’s own Sew Sew Social, which happens twice a month. Finally, they’re creating an online database to help people learn how to get involved with environmental initiatives near them.

Lewis is sympathetic to the way doing something about climate change can feel overwhelming in the face of the scale of the problem. But that doesn’t mean nothing can be done. “I think of drinking straws,” Lewis said. “There are all kinds of materials and solutions, and until people start complaining, those things don’t get implemented.” Lewis has asked her dentist to provide bamboo instead of plastic toothbrushes if possible, and for delis to wrap cheese in foil instead of plastic. “You make the step, but then you influence bigger people,” she said. A single backyard garden won’t move the needle. But what if there are a million backyard gardens?

Clymenza Hawkins

New Britain Chrysalis.

If one thinks of art as practice for life, the pieces in “Waste Management” can be thought of as people trying on the mindset of adapting to change rather than trying to push it back; of reimagining and reframing what the future — and for that matter, the present — can look like. “Art is a way of thinking about things,” Lewis said. “It’s not just about the finished product.” Talpade agreed. “Enjoying the process, what the process makes you feel — that is what you take out of the creative process.” The artist may not like the end result, or feel they can do better, but “if the process of creating has been something positive for you, I think that’s a successful project.”

That said, “in this show what I find fascinating is that the works here are so much like the raw material for my photographs,” Talpade said. “This is the kind of stuff that I go seeking when I go out.” We are surrounded by “trash and refuse,” but “give it to a creative, and they will create something out of it — which may repel you, but there is a fascinating beauty about it.… the way it’s put together, you can’t look away.”

In making pieces out of the scraps of something else, Lewis said, “You start to think about garbage in a different way. You start to think twice about throwing things away.”

Talpade and Lewis also have the gratifying sense of having tapped into a community of people concerned with environmental issues, from established artists and crafters to people who have just started to try to make things. Artists seeking to submit work “are always looking for shows that will fit their philosophies,” Talpade said. “I think they want to be together,” Lewis said, “We all like to meet and talk about what we can do.”

“There’s nothing wrong with anxiety, especially in the times we live in,” Talpade said. “Why would people feel comfortable with the climate disaster hovering over us? It’s not a comfortable situation! I’m all for making people anxious, if it’s going to make some action take place.”

“Waste Management: Reuse, Reimagine, Repurpose” runs at the Institute Library through January 2023. Visit the Institute Library’s website for hours and more information.