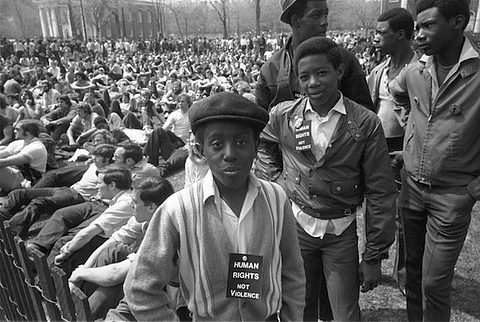

John T. Hill photo

On the Green, 1970.

Thousands of National Guardsmen gathered in the Goffe Street Armory, weapons of war in hand as they prepared to confront anti-war activists and Black Panther trial protesters on the Green.

But unlike at Kent State and Jackson State just a few days later, in New Haven, that violence didn’t come. A “conspiracy” of town and gown, Black and white, local and national players prevailed. The peace was kept, for the most part.

Fifty-three years later, the Armory — used as the National Guard’s staging ground for the May Day rally of 1970, a potential wellspring for bloodshed on that tumultuous day — was commemorated instead as a city landmark of the civil rights movement.

CT Freedom Trail Director Tammy Denease (center) at Friday's presser.

On Friday, local and state officials and historians and civil rights advocates gathered at Bethel AME Church on Goffe Street to officially designate the long-vacant armory at 290 Goffe St. as a site on the Connecticut Freedom Trail.

That’s the roughly three-decade-old map of 170-ish sites across Connecticut “that embody the struggle for freedom and human dignity” and celebrate the African American community, State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) Architectural Historian Todd Levine said at Friday’s ceremony.

New Haven already had 20 sites on the trail, including the 29th Colored Regiment Memorial in Criscuolo Park and the Amistad Memorial outside City Hall and the Grove Street Cemetery and the William Lanson statue on the Farmington Canal Trail.

The armory now marks New Haven site number 21. And, as Levine and Connecticut Freedom Trail Chairman Charles Warner and Director Tammy Denease explained, it also represents the first of four sites that make up a “trail within a trail” focused on the history of the Black Panther Party case in New Haven. (Levine said these four sites will be added to the Freedom Trail in honor of the late Paul Hammer, who advocated for their commemoration.)

Laura Glesby file photo

The Goffe Street Armory.

As explained at Friday’s presser by Paul Bass, the co-author of Murder in the Model City: The Black Panthers, Yale, And the Redemption of a Killer (and the founding editor of the New Haven Independent), the armory had a momentary role in one of the watershed episodes of the Black Panther Party, in New Haven and across the country.

That was the May 1, 1970 rally on the Green in protest of the murder trial of Black Panther Party leaders Bobby Seale and Ericka Huggins. The federal government sought the death penalty against Seale and Huggins for the Orchard Street murder of Alex Rackley, a 19-year-old alleged (but not actual) informant who was indeed tortured and killed by Black Panther Party members — but to whose murder there was little if any direct evidence to tie Seale and Huggins.

As civil rights and anti-war activists rallied by the thousands on the Green, the National Guard got ready at the armory on Goffe Street. They had grenades and other weapons, Bass said, and were given an order: that if they shot and killed someone on the Green, they would not be prosecuted.

Thanks to secret meetings being held at that very same time at the Yale president’s house among local Black activists, New Haven police, white activists from out of town, and others, “that day, besides tear gas in the air, was a non-event.”

Unlike at Kent State on May 4, 1970, when National Guardsmen shot and killed four unarmed student protesters in Ohio. Unlike at Jackson State on May 15, 1970, when police shot and killed two unarmed student protesters in Mississippi.

“We were the city that held it together,” Bass said.

Mayor Justin Elicker said that the Black Panther trial in New Haven posed a fundamental question that still resonates these decades later: “whether a Black American could get a fair trial in our city, in our country.”

The murder cases against Seale and Huggins were ultimately thrown out.

The National Guard on May Day.

Virginia Blaisdell Photo

Corner of York & Broadway, 1970.

Dori Dumas, the president of the Greater New Haven NAACP, spoke during Friday’s presser not just from her perspective as a local civil rights leader, but also as someone who grew up in New Haven during the civil rights movement, during the time of the Black Panther Party.

“We have to continue to tell the stories: the good, the bad, and everything in between,” she said.

Outside of the tragedy of Rackley’s murder, she said, her experience of the Black Panther Party was that “the Black Panthers addressed and advocated for children, spoke out against horrible housing conditions and policies, advocated for health clinics” in New Haven, and ran a “free hot breakfast program of which I personally benefited from.”

“I have fine memories of the Black Panthers,” Dumas said. “I recall them teaching us as children positive affirmations, like: Black is beautiful.”

She also spoke about how the armory was a “gathering place for events like the Black Expo” of 1972.

As he presented the mayor with the plaque officially designating the armory as a Connecticut Freedom Trail site, Warner spoke about the importance of “telling the stories that are may be controversial,” but that are true, and that should and must be remembered.

I was there on the green but not in the photo.