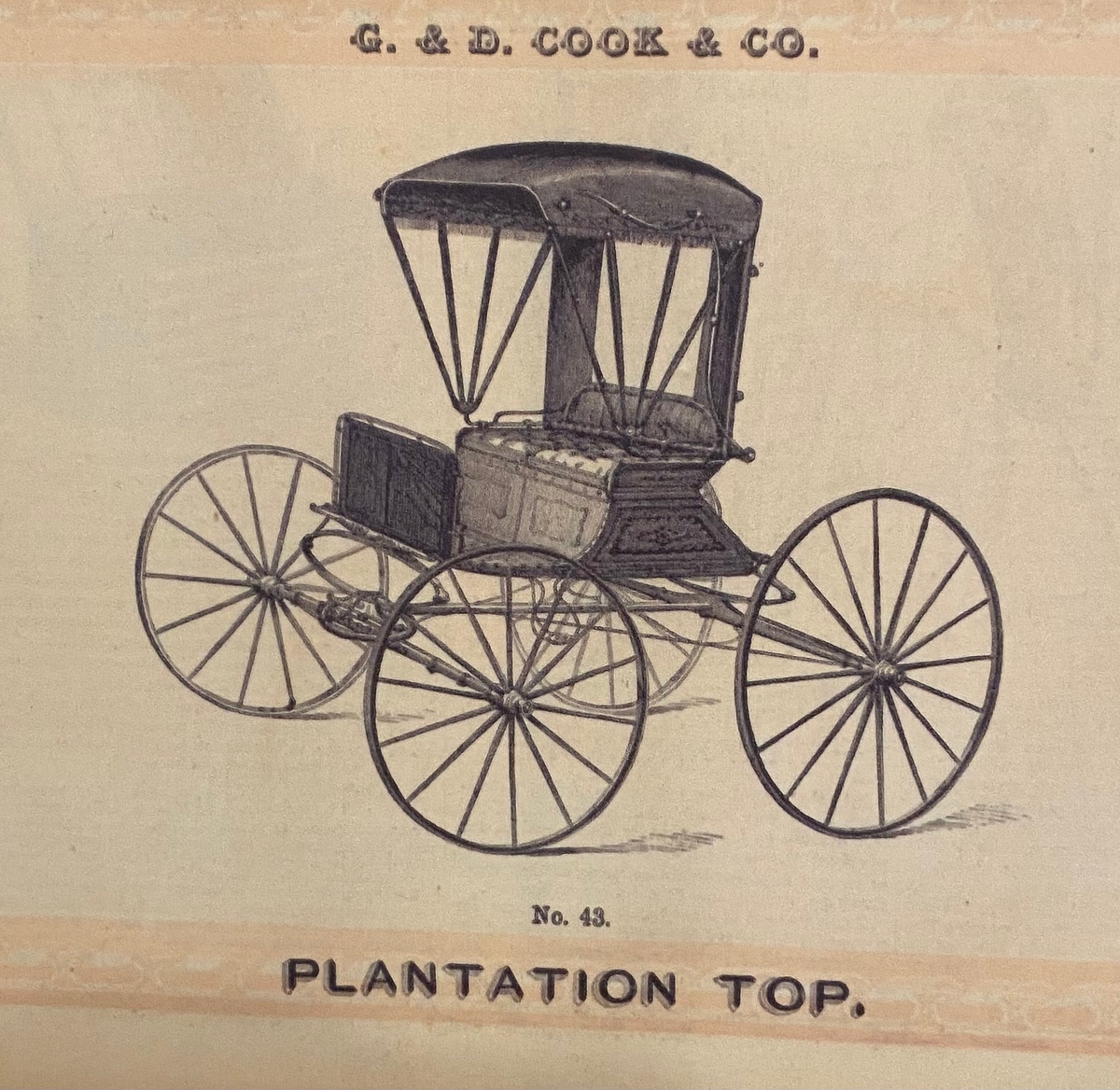

A New Haven-made carriage popular among Southern slave owners.

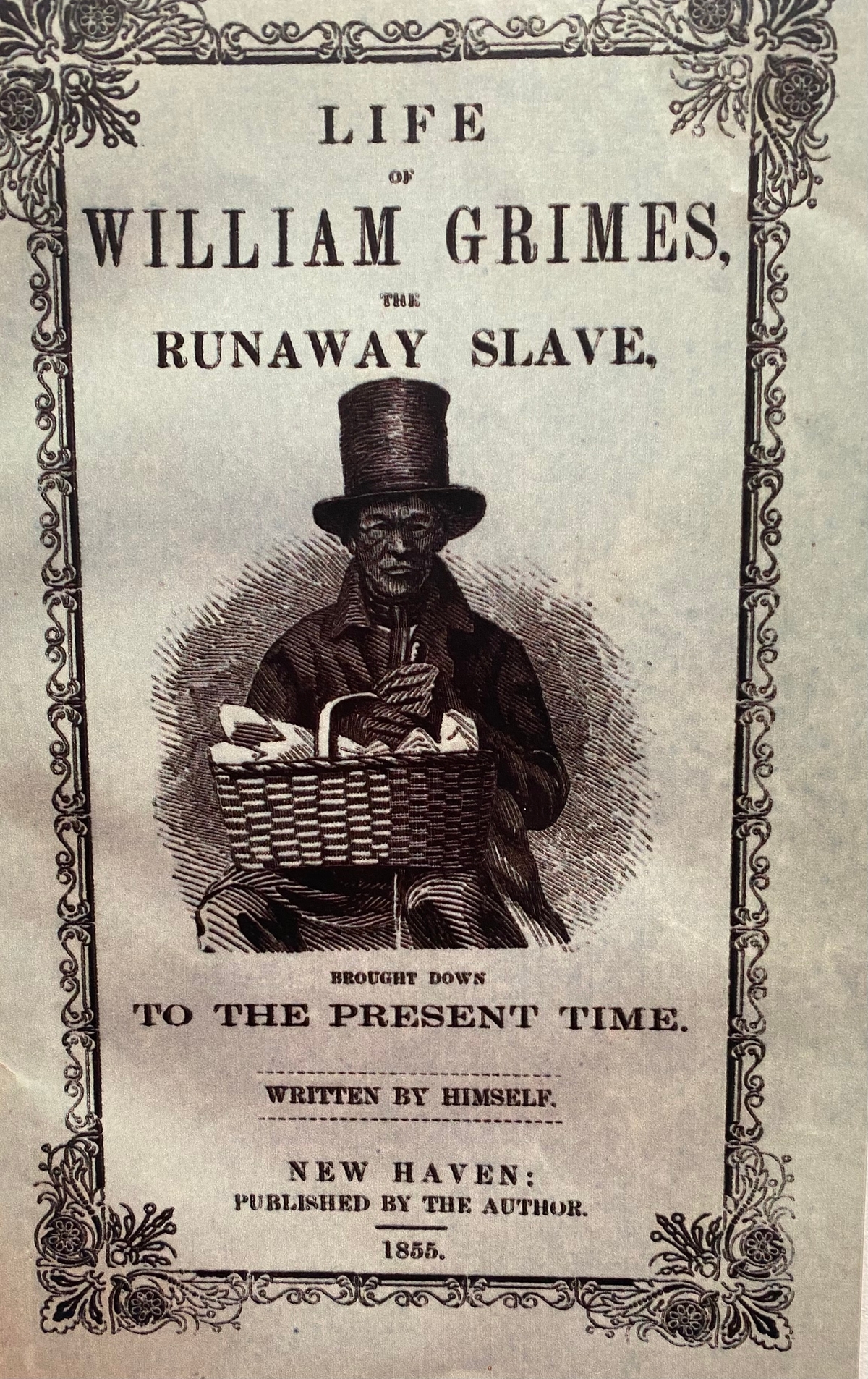

William Grimes escaped slavery on a ship from Savannah to New York, then walked to Connecticut. He published his autobiography months after he purchased his freedom.

(Opinion) Inside the New Haven Museum, I asked the greeter at the front desk about the reaction of visitors to the new exhibition.

“Many are shocked,” she said. “They had no idea.”

The exhibit, “Shining a Light on Truth: New Haven, Yale, and Slavery,” shows how the Elm City profited from America’s greatest shame, even depended on it, and when a chance came to right a wrong its leaders disgraced themselves further.

But to back up a bit, to before this new show and its companion book, Yale and Slavery: A History, both produced by Yale, to what was previously known.

Anyone paying attention, of course, is aware of the scourge of contemporary racism. On that issue, Nicholas Dawidoff’s blockbuster book, The Other Side of Prospect, documents its legacy in New Haven.

Before that the subject of Connecticut’s and our city’s record of institutional racism hadn’t been entirely ignored. For one, Complicity, written by Joel Lang, Anne Farrow, and Jenifer Frank, and published in 2005, revealed our state’s prominent role in slavery, and the wealth it brought to white citizens.

A key example of this chain of profiteering can be seen in the development of two products of the Elm City.

Eli Whitney’s cotton gin provided a mechanical way to remove seeds, an otherwise tedious and time-consuming task. In his effort to obtain a patent, he wrote to Thomas Jefferson in 1793, then the U.S. secretary of state, saying that enslaved people could process the product much quicker.

This new capacity turned cotton into the South’s most profitable export. And New Haven’s manufacturers of carriages seized on the opportunity.

At the time, New Haven was to carriage making what New Bedford had been to the whaling industry, with more than 60 companies producing four-wheelers aimed at the owners of enriched cotton plantations. The G. & D. Cook Company, known for its high-end carriages, introduced the lines Pride of the South, the Georgia No Top, the Plantation No Top.

That measure of lucrative distance from bondage, and profit from it, was cited by Hartford’s Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, who said, “Northerners have slavery just the way they like it: all of the benefits and none of the screams.”

Her comment, jarring as it is, skirts Connecticut’s own history of slavery, one of the themes in the New Haven Museum’s exhibit.

When I visited the first time, I almost overlooked a powerful element: a record of institutional ruthlessness.

An oak panel displays in intentionally haphazard fashion enlarged copies of local newspaper clippings from the slavery era, which in Connecticut lasted until 1848, when it became the last of the New England states to prohibit enslavement. The clippings advertised men, women and children for sale or offered bounties for escapees.

For example, an enslaver hoped to track down a 16-year-old freedom seeker, described here as “a wench,” in the common parlance of the time. Who was she? Did a local resident collect a reward? Or did the girl hide in fear for the rest of her life?

Yet the new book, Yale and Slavery: A History, goes beyond the cataclysms of slavery. The primary author of the volume is David W. Blight, a Pulitzer Prize-winning Yale historian. But it is also a group effort.

Chapter 6 was written by Michael Morand, director of community engagement at the university’s Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscript Library, who is also lead curator of the New Haven Museum exhibition. It recounts an event of mob mentality, deplorable then but also prescient.

Reading it today, noting the power of the politics of fear, it leaps right out of history and into the stream of denigrations of 2024.

The chapter covers what might have been in New Haven: the establishment of the nation’s first college built specifically for Black men.

The plan was discussed and endorsed in 1831 in Philadelphia, at a convention of Black intellectuals and abolitionists who decided on New Haven as the best option.

One of the reasons: It was already a center of higher education, as Yale was then the largest college in the nation, even as it restricted its student body to white, Protestant and of European descent. The city, too, grew more prosperous from international trade and in population, the 23rd largest in the nation.

But also because, “Its inhabitants are friendly, pious, generous, and humane.” And, “Its laws are salutary and protecting to all without regard to complexions.”

This was put to the test in 1831 as news spread about such a college, which was to be located at the corner of East and Water Streets, in the south end of the city. The opposition among the prominent society was swift and overwhelmingly negative.

The mayor, Dennis Kimberly, referred to the project as “a scheme” in an announcement of an emergency meeting of the city’s white property owners at the recently built State House. (New Haven was then the co-capital of Connecticut with Hartford).

The meeting was a raucous affair, stirred up in the late summer heat to mob mentality. After impassioned speeches, a vote was taken, its final tally seeming almost impossible in its one-sidedness: 4 votes in favor of the plan, 700 against.

The meeting’s published resolutions, in part, decried the emancipation of slaves, “in disregard of the civil institutions of the States in which they belong.” It asserted that educating colored people is “an unwarrantable and dangerous interference” with the practices of the southern states.

It went on to say, “Yale College, the institutions for the education of females, and the other schools already existing in this city are important to the community and the general interests of science, and as such have been deservedly patronized by the public, and the establishment of a College in the same place to educate the colored population is incompatible with the prosperity … and will be destructive of the best interests of the city.“

“Yale and Slavery” also cites this objection on the threat to the character of the city’s inhabitants: “That character would be threatened if the students of Yale are to be met by [Black college students] in all the pride of supposed equality, a threat also worrisome to the majority culture fearful that young ladies are to be elbowed at every corner by black collegians.”

Not to be dismissed here is the Yale influence, as the college was also against the idea.

Timed to accompany the release of Yale and Slavery and the exhibit, the school issued a formal apology for its connection to the slave trade, in part:

“Although there were no known records of Yale University owning enslaved people, many of Yale’s Puritan founders owned enslaved people, as did a significant number of Yale’s early leaders and other prominent members of the university community, and the Research Project has identified over 200 of these enslaved people.”

Many of those opposed to the Black college were among Yale’s early leaders. They could not have foreseen the eventual emergence of the HBCU movement, which has resulted in the building of 107 colleges and universities and, in effect, spreads the initial of inspiration of the New Haven effort: “Knowledge is power.”

The New Haven Museum show includes a gallery room designed as a library, showcasing scores of Yale’s earliest Black students and graduates, beginning in the late 1830s with James W. C. Pennington and a few others in the next decades, with more after the Civil War and beyond.

In the show’s guest book, a visitor from Atlanta, the aunt of two Black Yale graduates, wrote: “A wonderful exhibit telling the hard truths of the treatment of African Americans at Yale. Showcasing [who] succeeded despite all the challenges.”

That’s on the plus side. But we’d all have to be asleep not to hear echoes of racism in the present-day national politics of fearmongering.

In all of this, I thought of another city that has turned its historical shame into institutional apology.

In Charleston, S.C., a new International African American Museum has just opened, and tells the stories of the enslaved in a port city where the screams could be heard everywhere; where men, women, and children were sold, and where the fruits of their harsh labors were often enjoyed far north in cities like New Haven.

Guides, too, offer walking tours and are clear in their expressions of Charleston’s heritage of pain. So, another twist. That city, its original prosperity so tied to enslavement, has shown that in significant ways the South, even as prejudice obviously remains, is facing its past. Up here, in the “civilized” north, we are just beginning the process.

The New Haven Museum’s exhibition, “Shining a Light on Truth: New Haven, Yale, and Slavery,” curated by Michael Morand with Charles W. Warner, Jr., and designed by David Jon Walker, runs until the end of summer. Admission is free.

The logo that could have been.

It just never ends and some just don't want it to end.... like picking a scab over and over... the wound must never be allowed to heal; even if scarred, healing should be allowed some day or we can never move ahead to do better!